The concept of Black History Month is actually a telling one. It acknowledges that a there is a part of America’s story that is neglected for the remaining 11 but that for 28 days, we’ll get to the bottom of it with a list of heroic feats, flashes of genius and beautiful prose.

In actuality, the experience of Africans in this country lies at the core of its identity–the intensity of its aspirations, the cunning of its politics and the excruciating struggle toward its ideals. This raw center of America’s soul is so sensitive that the tendency to shield it is understandable.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard was the nerve center of America’s defense efforts for hundreds of years. Since joining its staff, I’ve indulged in the enormity of what’s taken place here–the mammoth construction, technological advancements and worker triumphs. Still it’s the missing faces that intrigue me, the ones lost to segregation and the notion that they weren’t relevant. Black History Month is less about race than it is an opportunity to probe my country’s heart and bowels.

The first ship built here, the USS Ohio, was part of the Africa Squadron—a U.S. effort to stem the tide of Africans being shipped as tools for use around the world. On the Brooklyn Navy Yard Overview Tour, I learn that Kings County was New York’s largest slaveholder. I imagine these unsung Africans laboring on and around the Yard, blooming outward from its shadow to anchor prominent communities like Weeksville, Fort Greene and Bedford Stuyvesant.

Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at BLDG 92’s permanent exhibit “Past, Present and Future” features a timeline that traces development of the area from early 17th century to now. One hundred years in I encounter a young Black man, John Forten of Philadelphia, who was a privateer on a ship captured by the British. He is held captive yet recovers to purchase the sail loft where he worked, becoming one of Philly’s wealthiest residents and a devoted abolitionist.

What was the source of Forten’s fortune, rising so far above the lot assigned him by his color? Was it his technical aptitude or a gift for diplomacy? Once he gained the means to escape a colored man’s reality, why didn’t he? Was its cruelties too personal or his character too pure? Does not knowing these things impact my ability to navigate through life in some way?

Better documented in BLDG 92’s “Building a Modern Navy” exhibit on the third floor are the stories of Robert Hammond and Clarence Irving, African-American veterans who describe the segregation they encountered. A trained medic, Hammond was initially banished into the kitchen to preserve the sanctity of the white female nursing corps. Irving followed his father and brother onto the Yard to become a rarefied Black machinist. His patriotism and grace ring familiar to me but never fail to inspire a sense of awe.

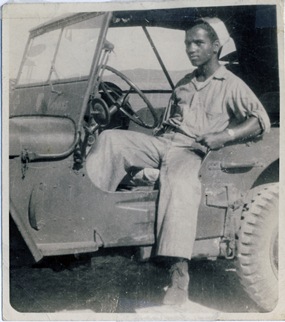

This month, BLDG 92 will display the work of the late Wesley Fagan, an African-American man who worked his way up from a messenger to become the Yard’s first Photographic Director. A savant, Fagan amassed both an impressive jazz music resume, accompanying greats such as Dizzy Gillespie and Noble Sissle, and an image portfolio of international VIPs, presidents and famous ships–including the fiery USS Constellation where dozens perished and the Yard’s closure was fated.

The Navy Yard saga is a timely opportunity to contemplate the costs and rewards of being an American.

BLDG 92 is open Wednesday-Sunday from noon to 6pm. The Brooklyn Navy Yard Overview tour takes place weekends at 2pm. Tickets and details are available at BLDG92.org.

Kenya Solomon is Coordinator of External Affairs for the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation where she works on marketing and development for BLDG 92.

Kenya Solomon is Coordinator of External Affairs for the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation where she works on marketing and development for BLDG 92.

Not in our backyard! Dyker rallies to prevent ‘out of character’ nine-story building from being built

Not in our backyard! Dyker rallies to prevent ‘out of character’ nine-story building from being built  Housing going up at Angel Guardian Home site: School also slated to be built at location

Housing going up at Angel Guardian Home site: School also slated to be built at location