A Friday night forum on diversity in schools and the fate of the Specialized High School Admissions Test made clear how a bulk of southern Brooklyn parents and educators feel about the mayor’s proposal to eliminate the exam.

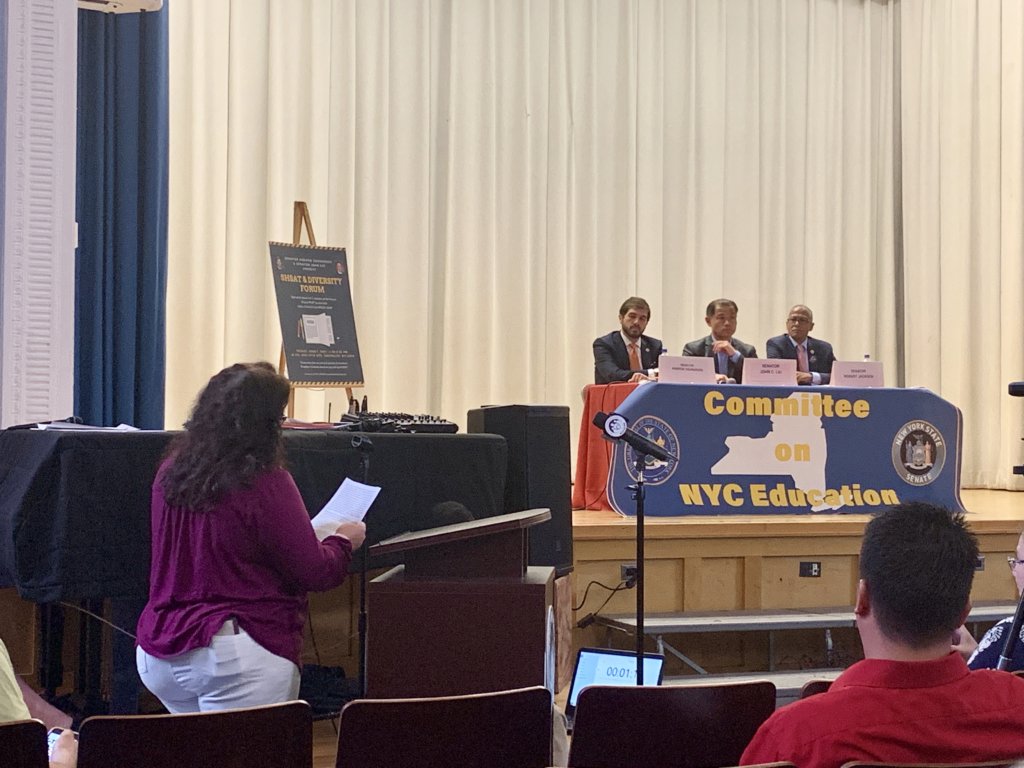

The June 7 event, hosted by State Sens. Andrew Gounardes, John Liu and Robert Jackson, packed the I.S. 201 auditorium in Dyker Heights where, for two hours at the start of the weekend, parents, educators and even kids testified, primarily in favor of the test.

The SHSAT is currently administered to eighth and ninth-grade students in order to determine admission to all but one of the city’s specialized high schools. Of the nine elite high schools in the New York City public school system, eight use the SHSAT as the sole criteria for admission.

The mayor and Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza are pushing to eliminate the SHSAT in hopes of upping racial diversity in the top high schools like Brooklyn Technical High School and Peter Stuyvesant High School, which currently enroll low numbers of black and Latino students.

The incoming freshman class at Stuyvesant High School, for example, has only seven black students, according to Chalkbeat. Yet, black and Latino students make up 68 percent of the overall population in New York City schools, according to the Mayor’s Office.

Under de Blasio’s plan, the SHSAT would be replaced by a new enrollment system that would allow the top seven percent of students in each of the city’s middle schools to gain admission to specialized high schools.

But Asian-American parents, whose children make up a large percentage of the student population in specialized high schools (more than 60 percent), and who made up a large part of Friday night’s attendees, have said they see the administration’s plan as an attack on kids who work hard to ace the SHSAT.

“No student in the city is denied the freedom to work hard and get into a better school,” said the first speaker, Leong Cho, who maintained that, while diversity is important, eliminating the SHSAT, which Cho called a “completely objective” gauge, isn’t the solution.

“And no parent is also denied [the freedom] to spend more time or resources to help his or her kids get into a better school,” Cho added.

Nearly all subsequent speakers echoed Cho’s concerns, including Community Education Council 20 President Adele Doyle and Christa McAuliffe Middle School Parent Teacher Organization President Vito LaBella, who equated the disparity displayed by specialized high schools with a lack of preparedness throughout the city.

Instead, both called for the focus to be shifted to the city’s gifted and talented programs. (There are currently bills being heard in both the Senate and Assembly committees that would require the New York City Department of Education to create more gifted and talented programs and classes.)

Referencing his past experience with the NYPD, LaBella told audience members, “When the Guardian Angels wanted to patrol the subways for free, they were told by the city and the unions that they couldn’t do it, because the city and the police unions wanted to put politics over the safety of their officers and politics over the safety of the public.

“Fast forward 40 years and what’s changed?” he went on. “The DOE is now putting politics above children.”

The SHSAT encourages a “work ethic to which every student in the city should aspire,” according to Doyle. “To say that our public school system is good enough is to deny the fact that only 37 percent of our public high school students [are] deemed college-ready compared to the 100 percent of students who graduate from specialized high schools.”

This was the second southern Brooklyn forum on the topic. It came on the heels of a June 1 meeting with parents hosted by Assemblymember William Colton — who was at I.S. 201 on Friday, and who taught in the public school system for 11 years before entering politics — to brainstorm ways to keep the SHSAT in place.

“The test is objective. You can’t get into Brooklyn Tech because you know somebody,” he has said.

Gounardes told this paper in a statement that he is committed to hearing residents out on the issue. “The quality of a child’s education is of profound importance to any family, and every family deserves the best — beyond the relatively narrow scope of specialized schools,” he said.

“Simply eliminating the SHSAT would disproportionately target first- and second-generation immigrant families. Instead, we need a comprehensive approach to ensure diversity in public schools and address the fundamental disparities in our education system. Free public education from pre-k through college would be a big step in the right direction.”

Despite what appears to be constant pushback to the mayor’s plan, a Quinnipiac poll released earlier this year showed broad support for overhauling the admissions process. In it, 63 percent of New York City voters said they favored admissions changes to boost diversity, with 57 percent on board with scrapping the entrance exam entirely.

“The admissions process to New York City’s top high schools has become a lightning rod. And New Yorkers say rethink it. They favor considering other factors besides acing a standardized test as the only door to entry,” said polling analyst Mary Snow.

Additional reporting by Paula Katinas.

On the Avenue: Troop 18G honors 2nd Eagle Scout

On the Avenue: Troop 18G honors 2nd Eagle Scout  Students shine in ‘Charlie Brown’ musical!

Students shine in ‘Charlie Brown’ musical!