Howard “Duke” Davis, one of the oldest living minor league baseball players, died in September of natural causes in Vestal, N.Y. He was 97.

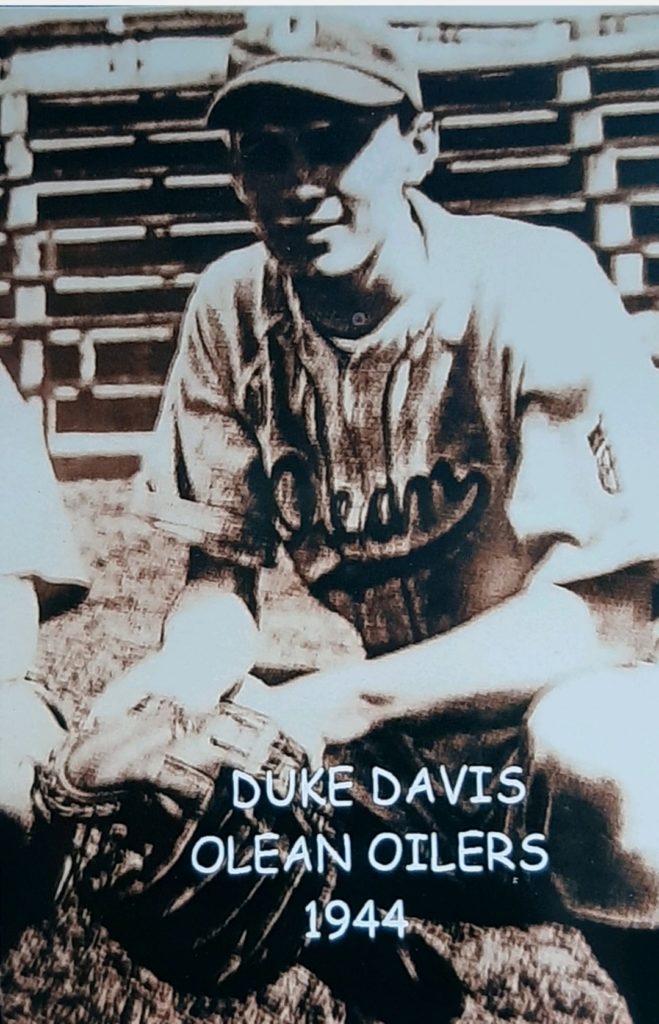

Davis was a catcher for the 1944 Olean Oilers, the Brooklyn Dodgers’ full-season Class D affiliate. Unlike the Dodgers’ Duke Snider, who received his nickname from his parents, young Howard Davis earned his moniker on the sandlots of Vestal when he responded to “Duke” for a pick-off throw to first base.

Davis carried his love of baseball from the sandlots to the Vestal High School team and graduated with letters in baseball, basketball, football and track. In 2005, he was inducted into New York State’s High School Section IV Hall of Fame.

After high school, he worked for IBM and played in the company’s Industrial League, where he hit .361 and caught the eye of Brooklyn Dodger scout Jake Pitler. Despite some family objections, the 21-year-old signed a contract with the Dodgers, received a $500 bonus and hopped a train to Newport News, Va., for spring training in March 1944. He returned to western New York a month later to play for the Olean Oilers of the Pennsylvania Ontario and New York League (the forerunner of the New York Penn League), 160 miles west of Vestal.

Duke Davis was signed as a catcher by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1944 and played for the Class D Olean Oilers of the PONY League.

Photo courtesy of the Olean Oilers

Unlike today’s minor leaguers, PONY League players did not travel in a luxury coach bus to their next destination. Players took shifts driving the team’s two station wagons, which carried all 18 players to the next town. They drove hundreds of miles to play in the towns of Erie and Bradford, Pa., and Hamilton, Ontario, Geneva and Lockport, N.Y.

In the dugout, Olean players drank water from a bucket with a ladle, while their locker was just a nail on the wall along with an offer from the team trainer to put their wallets in a locked toolbox. Uniforms often consisted of hand-me-downs from Brooklyn, and Davis even received Dodger manager Leo Durocher’s pants.

His most cherished hand-me-down, however, was a customized helmet that was made for outfielder Pete Reiser, which he received after he sustained a concussion behind the plate. Seventy-six years later, the helmet – one of the first introduced to the game of baseball – is still a prized possession of Duke’s son Brad.

After the concussion, Davis also broke the thumb and pinkie on his throwing hand and his season was cut short. He tried to come back in 1945 with the Thomasville Tommies in the Carolina League, but further injuries ended his career.

Although he never returned to professional baseball, a number of his teammates went on to play for the Dodgers. His roommate, Bobby Morgan, became Pee Wee Reese’s backup at shortstop, while relief pitcher Jack Banta was a big contributor to Brooklyn’s 1949 pennant. George “Shotgun” Shuba made history in April 1946 as the first white man to publicly congratulate Jackie Robinson as he crossed home plate after hitting his first professional home run in Jersey City, a moment referred to as “The Handshake.”

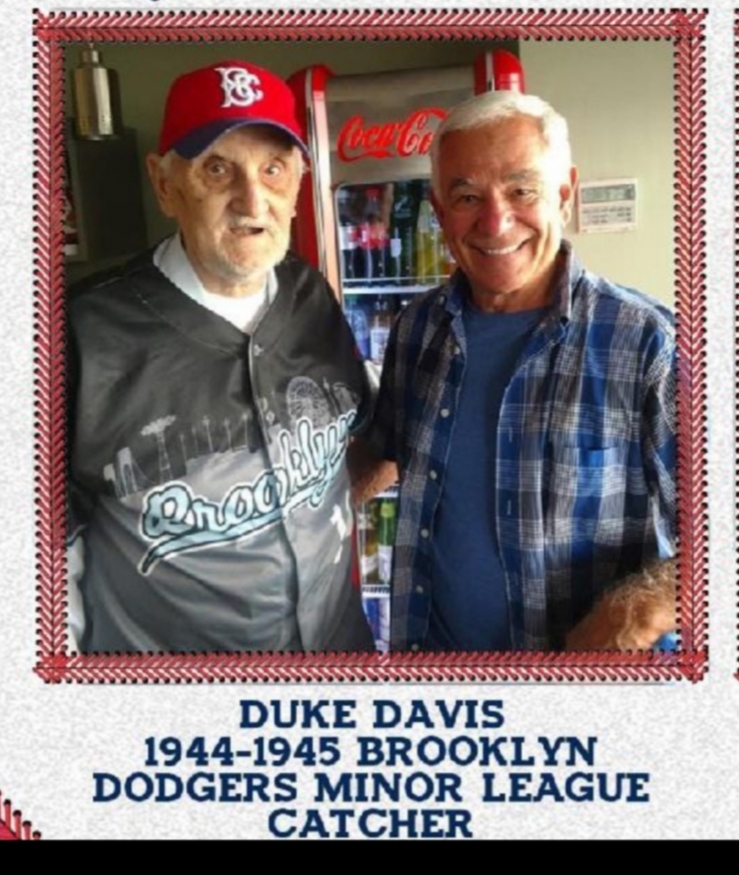

Former Mets manager Bobby Valentine, right, with Duke Davis during a Double-A game at the Rumble Ponies Skybox in 2018.

Photo courtesy of the Binghamton Rumble Ponies

After baseball, Davis worked for New York State as part of the team that surveyed downtown Albany for the new state capital mall that was built in 1960s. He became a rabid fan of the Double-A Binghamton Mets when the team moved there in 1992. After years of following the B-Mets, he was given a lifetime box seat behind home plate, where he enjoyed meeting baseball scouts like Mike Toomey of the Kansas City Royals.

At a memorial service at the Vestal United Methodist Church, Pastor Mike Willis kept his promise to Davis and had the organist play “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” – a fitting sendoff for the last inning of an old ballplayer.

Moore marches past Fontbonne to state championship

Moore marches past Fontbonne to state championship  Returning Tigers set to kick off football season

Returning Tigers set to kick off football season