From brooklyneagle.com

Thousands of trees were uprooted across New York City in Tropical Storm Isaias on August 4.The city’s Parks Department received more than 21,000 service requests for street and park trees following the storm; Queens and Brooklyn were hit the hardest.

Several decades-old giants were felled in tree-lined Brooklyn Heights, including a honey locust that stood for roughly 70 years at the entrance to the Promenade, at the foot of Montague Street. Two blocks away, a giant London plane tree smashed through a cast iron fence and a brick wall on Hicks Street near Grace Court. Three large trees fell in backyards along Grace Court, one breaking third-floor windows; several more came down in Brooklyn Bridge Park.

According to the US Department of Agriculture, the tree canopy covers 21 percent of the city — but only 16 percent of Brooklyn, less than any other borough. Many of Brooklyn’s trees are in brownstone neighborhoods like Cobble Hill, Park Slope and Brooklyn Heights.

These shady streets didn’t come about by accident. In Cobble Hill, hundreds of trees have been planted by the Cobble Hill Tree Fund. The Park Slope Civic Council works with the city and local merchants to plant trees.

The granddaddy of Brooklyn’s neighborhood tree stewards may be the Brooklyn Heights Association, which has planted and nurtured trees for most of the past century. There are 1,618 street and park trees in Brooklyn Heights, in a neighborhood of roughly a third of a square mile in area. Most were planted by the BHA. In the 1940s, the group planted 1,081 trees, mostly London planes, and has added 46 more in the years since.

Photos taken before the trees were planted show a starker, less welcoming Brooklyn Heights.

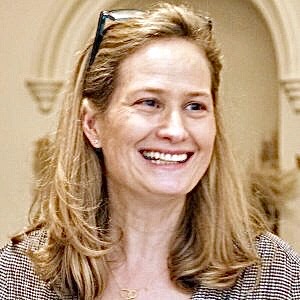

“Look at the old photos,” Erika Belsey Worth, BHA president, told the Brooklyn Eagle. “The streets were baking. Now, when you walk in Brooklyn Heights, it’s cooler because of the shade.” In addition, the air is cleaner and the greenery gives people a psychological boost, she added.

But time and weather take their toll on the neighborhood’s trees. Some blocks, such as Clark Street between Willow Street and Columbia Heights, have lost numerous trees, leaving behind “weirdly empty tree pits,” Belsey Worth said. The London planes the BHA planted in the ’40s are now “at maturity and beyond. We’re due to give some tender loving care to these trees.”–>

The importance of trees to New York City can’t be overestimated. Roughly 7 million of them across the five boroughs make up an urban forest, providing not only beauty and character to neighborhoods, but millions of dollars in health and economic benefits. The trees soak up rainfall and prevent flooding, clean the air, sequester carbon and cool their surroundings. London plane trees alone remove more than 77 tons of air pollution each year, according to the Parks Department.

A multigenerational effort

In the Heights, taking care of the trees is a tradition extending through the generations. Sidewalk trees have always been “a top priority” for residents, said Judy Stanton, who served as executive director of the BHA from 1989 to 2015. During her 26 years heading the organization, members continually donated to the BHA Tree Fund, “and significant amounts were donated by film shoot crews when told how their contributions would be spent,” Stanton said.

The BHA maintained a strong partnership with the Parks Department’s Forestry Department staff, Stanton recalls.

“BHA organized volunteers for two [Parks] tree census projects, surveying and documenting the conditions of the neighborhood’s trees … During my years, the BHA invested a total of $68,000 toward street tree pruning contracts. And in 2007 and 2014 we planted new trees.”

Peter Bray, BHA executive director from 2015 to 2019, oversaw a program that helped residents enlarge tree pits. (Read an interview with Inger Staggs Yancey, BHA’s liaison to the Parks Department, here.)

“Since the city was funding tree planting and pruning, the BHA filled the void with regard to enlarging tree pits that were effectively strangling the roots of so many of the trees that add to the beauty of the Heights’ streets,” Bray said. He credited Katherine Davis, the BHA’s membership and communications manager, with spearheading the program.

The new generation moves it forward

Lara Birnback, BHA’s current executive director, told the Eagle that the tree pit program was moving forward after a delay caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“In fact, we are hoping to launch a new effort this fall to conduct an inventory of the conditions of our tree pits and trees. We think this is a great activity that people can undertake as they plan socially distant walks around the neighborhood,” Birnback said.

“We’re also hoping to recruit some ‘block captains’ or tree stewards who will volunteer to monitor the trees on their block and care for any new trees in particular that may be planted,” she said.

And now there’s a website

The new generation has brought technology to the tree game, Birnback said.

BHA volunteer Peter Steinberg has built a website that tree fans can use to easily record tree pit data. All people need in order to participate is a tape measure and a smart phone.

“I created a database to write down all the information about every tree pit in Brooklyn Heights,” Steinberg told the Eagle. He estimates that there may be roughly 4,000 tree pits in the neighborhood. On Grace Court there are 37 pits on just one block alone, he said.

Last week Steinberg taught his two young sons about the importance of trees and how to measure the pits.

“One way we can take care of the neighborhood is to make sure there are as many big healthy trees as possible. But they need help,” he explained to Charlie, age 8 1/2, and Henry, age 6 3/4. “If a tree pit is big, water can get into the dirt and the tree can grow. But if the tree pit is tiny, not enough water gets to the roots and the tree might die.”

Henry thought the project was “kind of cool. I really like trees because they can have all sorts of leaves,” he said. He added wistfully, “Though I’ve never actually seen a smelly ginkgo tree.”

Charlie also approved of trees. “Trees can have really good stuff to eat on them,” he said, noting that he’s been to apple orchards.

Steinberg said he created the website because “I live in Brooklyn Heights. I’ve been here 20 years and somebody has to take care of Brooklyn Heights. Why not me?” The website can be adapted for other neighborhoods that also wish to use it, he added.

The BHA contributes a percentage of the funds necessary to help property owners enlarge too-small tree pits, Davis said. It also takes much of the hassle off the shoulders of the homeowner.

“We try to locate at least six tree pits on the same block,” she said. “We can find a contractor to do them all at once. The contractor gets the permits from the Parks Department and Department of Transportation. We get the Landmarks Preservation Commission permit.” This saves homeowners the $700 the contractor would charge to file required plans and photos with Landmarks, Davis said.

On top of those savings, BHA’s will contribute 50 percent, up to $350, of the cost of cutting and removing the concrete and adding topsoil or mulch.

Honey locusts near the end of their run

A honey locust’s natural life span averages 120 years, according to the Parks Department.

But honey locusts don’t live as long in the urban environment, said Koren Volk, a volunteer with BHA’s Promenade Garden Conservancy. The honey locust that blew over in the storm was likely planted in the 1950s, along with the other honey locusts planted along the esplanade, she said.

“70 years is old for a street tree,” Volk said. “There are several on the Promenade that are in rough shape, and some should probably come out. Parks will have a challenge.”

Honey locusts are “wonderful street trees,” she added. “They have small leaves so they don’t act like a sail in the wind. But these are really at the end of their useful lives.”

If you want to get involved with the tree pit program or other BHA activities, contact [email protected].

Brooklyn’s Great Trees

In the 80s, the Parks Department asked residents to nominate their favorite “Great Trees.” These so-called “heritage trees” bring benefits valued by the Parks Department at more than $25 million.

One Great Tree is a magnificent dawn redwood at 151 Willow St. in Brooklyn Heights. It is 100 feet high and as straight as a poker. Many people walk right by without noticing it — until they look up and see it towering over the low-rise neighborhood.

This is the favorite tree of Lara Birnback, executive director of the Brooklyn Heights Association.

“I’m a native Californian so the redwood really speaks to me,” she told the Eagle.

Another Great Tree is a 57-foot-high southern magnolia at 677 Lafayette Ave., planted in 1885. Saved from the wrecking ball by Brooklyn “tree lady” and local activist Hattie Carthan, the tree is Brooklyn’s only living landmark.

Other official Great Trees reside in Prospect Park. One is the famous Camperdown elm, a gift from Mr. A. Burgess in 1872. It is one of the few elms in the world grown from the Earl of Camperdown’s Scottish estate. When Prospect Park — and the elm — fell into disrepair, poet Marianne Moore campaigned for the tree and its park, and helped start the Friends of Prospect Park.

In 1967, she wrote a poem in the Camperdown’s honor. “We must save it. It is our crowning curio,” she wrote.

The largest tree in Brooklyn discovered during the Park Department’s 2015-2016 tree census is a 61-inch-diameter London plane tree on East 5th Street near Avenue N in Midwood.

Sunset Park residents look to form new mural at 54th Street

Sunset Park residents look to form new mural at 54th Street  Man charged with attempted kidnapping after allegedly grabbing six-year-old in Coney Island

Man charged with attempted kidnapping after allegedly grabbing six-year-old in Coney Island